A Right Charlie to Foster Victorian Cycling

Melbourne, Victoria

Welcome to Episode 2 of transcripts from our influencers! podcasts, talking to people making a major difference to cycling or micromobility in Australia and around the world.

We’re looking back at the interviews we’ve done over the past 12 months and today we’re featuring Melbourne-based Charlie Farren, who has spent a lifetime cycling and encouraging many others to ride.

She’s the founder of iconic mass participation cycling events including Around the Bay in a Day and the Great Victorian Bike Ride.

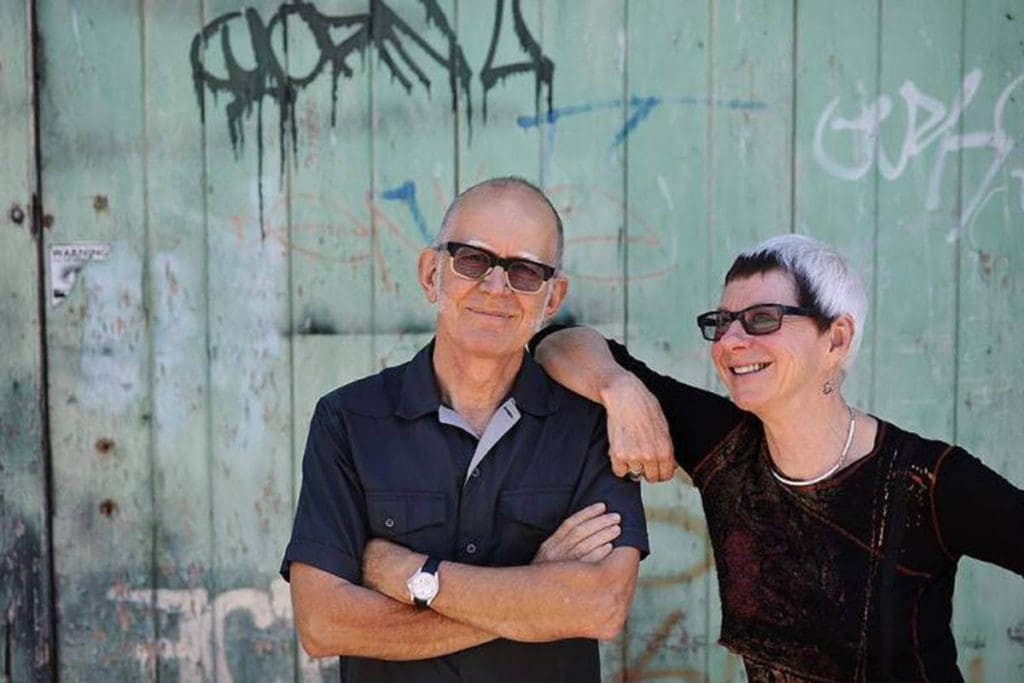

Charlie also volunteered her considerable organisational skills as a director of the Amy Gillet Foundation and Cycling Australia, now AusCycling. As president of what was then Bicycle Victoria, Charlie transformed what was once a tiny, cash-strapped organisation into one of the largest cycling organisations in the world, working with her late husband Paul and others.

Paul and Charlie also created the Farren Collection, one of the world’s best collections of vintage bicycles.

She has brought optimism, enthusiasm and a wonderful dose of British eccentricity to all of these many and varied roles.

Micromobility Report: Not too many ladies go by the name Charlie. Was that something given to you by your parents or something you decided?

Charlie: Goodness no. My mother never ever used that nickname, but I picked it up in Britain where I grew up. There’s a saying to ‘be a right Charlie’, to play the fool, and I think that’s the category I came into. When I joined a cycling club in my early teens, I was the only female. I don’t think the blokes liked that very much. I got a male name and it stuck with me all these years.

MR: Please tell me the name of that club because it has a wonderful name.

Charlie: The Mitcham and Tooting Cycling Club. I lived in South London, and it was a touring club. I’ve never really raced but I’ve done time trials and puffed up hills behind guys in leather shorts and at the time they were smoking pipes too.

MR: As your accent gives away already, but you’ve now readily admitted, you don’t come from these parts.

Charlie: Hey look, I’ve been here longer than I’ve lived in the UK, decades! I think it’s a wonderful place. As long as you can escape from time to time.

MR: Your first trip from England to Australia, you chose a rather unusual form of transport.

Charlie: It was the wonderful Morris Minor four-door deluxe, that failed the MOT, the inspection in Britain. I bought it from Uncle Eddie for 10 quid and the back had rusted out. You could put your feet through the floor at the back, but we chose this.

were going to do the grand overland trip and then go back to London to resume our lives, and we were going to do this in the Morris Minor. We set off with a box on the roof with all the tools and we took the back seats out so we could sleep in the Morris Minor. We had a stunning budget for the year of £500, that was it. We had some adventures. A lot of adventures.

MR: How far did the Morris actually get? Where was it left behind?

Charlie: It got all the way through to Nepal, having had quite a few adventures on the way. We got arrested in a couple of places. In Pakistan we got into Rawalpindi and this little car almost smiled, because having been a lone voyager for all those months, all the taxis in Rawalpindi were Morris Minors. Suddenly it was amongst all these friends chuffing around.

We got to Nepal and we knew by that stage we were going to go further and fly to a couple of places. We sold this decrepit little Morris Minor to somebody that was heading back to the UK. For all I know it’s still shuttling backwards and forwards to the UK.

Magnificent Collection

MR: This magnificent backdrop, we should talk about this before we go much further.

Charlie: It’s a magnificent collection, which was the passion and obsession of Paul. I’m bicycles, through and through, but he was the collector. It’s of a particular period, about 1860 to 1900, which I think is the most interesting when you look at bicycle history because it’s when all the developments to the bicycle occurred.

The first, what we would call a bicycle was about 1817. We’d had a wheel from 3500 BC but it was only ever used for utility purposes, maybe grinding corn or a potter’s wheel.

There was a German landscape gardener, Baron Von Drais, who got sick of walking around these huge estates. He put one wheel behind another, worked out some steering mechanism, hadn’t got round to thinking about pedals. It was a running machine.

You got the beginning of what we now know as a bicycle. The essence of it was steering. If you left the steering lock on, early bikes had steering locks, you couldn’t ride it. You have got to be able to make those micro-movements all the time.

In 1817, you’ve got this two-wheeled thing, a hobbyhorse, called a Draisine. It was taken up with a vengeance. It was a real craze throughout Europe and Britain and all the elite at the time, who had been encased in carriages. All these great floppity old blokes who have only ever moved around in carriages went out onto the streets on this machine.

They were ridiculed. The cartoonists of the day made fun of them, so it was a brief craze, it flared and it died.

Forty years went by, and then you got something called a velocipede … a bone shaker. That came about because somebody found one of these old hobbyhorses, looked at it and thought: “If I put something on that front wheel, I could take my feet off the ground. I could push the front wheel around.”

We’ve suddenly got pedals onto a front wheel but the wheels were still small. You’re a tall athletic person and you’d have said to a maker: “I want to go further and faster because when I turn that pedal, all I do is go the circumference of that wheel. Make that wheel bigger, please.”

This is a very potted history of cycling, but it’s the essence of it. That front wheel was made bigger and bigger and bigger. Then you got things like the penny-farthing because it was these athletic elite aristocratic young men who wanted to adopt them. In Australia we were early adopters, we were rich in the Victorian era.

In the next 40-year period, all the developments of gearing, rear-chain drive, occurred; until you got to the point where you had a diamond frame, pneumatic tyres and it would pass for a modern bike but it might still be 120 years old. This collection, it’s stunning. We didn’t have kids we had bikes, I always said.

It took passion, obsession and a bit of money to put this together, and it’s world-class and it’s very unusual.

MR: If people want to see the collection, there is a part of it available for the public to see.

Charlie: A portion of the Farren Collection is at the MOVE Museum in Shepparton – the Museum of Vehicle Evolution.

It has a very good representation of the Farren Collection up there.

Here is a private collection. Happy to open it for groups but it’s not a public space.

I’m looking directly at a quote from Iris Murdoch and it’s telling me: “The bicycle is the most civilised conveyance known to man. Other forms of transport grow daily more nightmarish, only the bicycle remains pure at heart.” Living in the middle of a city, I can only wholeheartedly agree with her that other forms of transport grow more nightmarish daily.

I do think that the bicycle is such an appropriate vehicle for so many journeys that people currently do by car. It gives you such flexibility. It’s fantastic.

MR: You’ve got a quite diverse fleet of personal vehicles. How do motor vehicles fit into your mix of personal transport versus bicycles?

Charlie: For me, transport is a tool to achieve journeys basically, and you have to use the appropriate tool. Public transport, great: taxis, airplanes, trains, buses, trams. Flexibility comes with the motorcar sometimes, but not always; longer distances, door-to-door, if you’ve got people who are compromised and can’t use public transport. But the bicycle for me is my first go-to vehicle, because I live in the middle of a crowded city and most of my journeys are short journeys.

I’m a transport cyclist but I also love going out on longer rides. I’ll cycle across Europe, or I’ll cycle down in Tasmania. Or Beach Road, a favorite in Melbourne, everybody knows that, and it’s a buzz.

You can get transport, you can get fitness, you can get enjoyment, and you can improve your quality of life. My fleet of bicycles fits into my smorgasbord of transport if you like. I’ve got a van, which of course is good for carrying bikes.

I’ve got the usual, I’ve got a road bike, I’ve got a mountain bike, I’ve got a folding travel bike. I’ve got a four-seater for having fun on. I’ve got quite a few bikes.

Launching Iconic Events

MR: You haven’t just been content to ride bikes a lot, you’ve also started a lot of bike rides and created a lot of events over the years.

Charlie: It’s my default position, organizing. It’s like ordering everybody around all day, it’s fantastic!

I’ve been involved and sometimes instrumental in starting some of the iconic events in Australia. Down here in Victoria in the sesquicentennial year (1984/5), we wanted a bicycle event because everything that was being proposed had nothing to do with bicycles. That was the genesis of the Great Victorian Bike Ride. Prior to that, I had been involved with the Melbourne Bicycle Touring Club, and we’d started our own one-day ride called the MAD ride, Melbourne Autumn Day tour.

The MAD ride was a one-day ride with entertainment. It was meant to be fun. I believe that events should be something you can’t do by yourself. It’s not just organising you to ride 50, 100, 200km, but organising something you couldn’t do yourself.

All the original Great Victorian Bike Rides had an element that you couldn’t have done by yourself. We got rafts built to cross the Murray River one time because we couldn’t get across where we wanted to. That came absolutely unstuck because it was a really wet day where we landed. The banks were so muddy. We had all these people trying to scramble up the banks, slipping and sliding around all over the place.

We went up to Rutherglen. We had to extend the platform for the train which was carrying all the riders and their bikes. We stopped the train so we could have a Ned Kelly hold-up at Glenrowan.

MR: It sounds like a Charlie Farren touch. I suspect that was your idea, that hold-up.

Charlie: Lots of things are achieved when there are a group of enthusiasts. All those early rides, the Great Victorian Bike Ride, the Great Melbourne One-Day Ride, the Easter Bike, Spring Bike, Around the Bay in a Day … it took the energy and enthusiasm of a group of people. Sometimes I can provoke and encourage that enthusiasm, but you have to have more than one person.

The rides worked because we had this incredible number of volunteers and the rides out there still run with that volunteer component.

I’d interview these volunteers and they might be a train driver and have nothing to do with bikes, but they’d have that enthusiasm. If I could see the light in their eyes, I thought, “we can place you somewhere”. was a rather dull looking sort of guy and I thought, “Oh, what I’m I going to do with you?” He was an accountant. He just looked at me and said, “I’m yours for the year”. It was that phenomenal commitment of “whatever I can contribute, you can have it”.

Some of the big rides around the country have failed or closed, and the private sector’s stepped in. They don’t work with quite so many volunteers but it’s still an essential component.

MR: Of all those rides, which would you say is your proudest achievement?

Charlie: It would have to be the Great Victorian Bike Ride, because we set up systems to move a town. We had 5,000 people, and when we started that very first year, we started not knowing the logistics that would be required. We had a very steep learning curve from that first year.

If you’ve camped overnight, the first thing you want to do in the morning is use the toilet. There were no toilets to hire, so we had to build them. We had all the orthodontists and lawyers building toilets, building washing facilities, building shower blocks, building a kitchen container we could serve 5,000 meals within an hour from.

If you came to me and said “I’m quite good at running radio stations”, I’d think, “Okay, we’ll have radio station but you’ll be responsible for it. I might give you a smidgy little bit of money but not very much.”

We added things to the ride. We added medical massage. One year, we had spas, because somebody said “what do you need on this ride is spas”. He came along with all these trailers with spa baths on the back.

The same guy, the following year – he was a stockbroker but he’d been on a couple of these rides and was wildly enthusiastic – he said, “Getting your washing done is the big problem. I reckon I could contribute to that. I’ll get my semitrailer license and I’ll get some industrial washing machines, put them in there, and every day people can give me their washing, and I can have it done and back.” He did this.

The ride was nine days. After about four days of zero sleep, this walking skeleton said: “I think I have bitten off more than I could chew.” That never happened again. Five thousand people wanting their washing done overnight, that’s a tall order.

If you thought that it would contribute to the ride, we would enable it – radio station, newspaper, massage, whatever it was. We wanted to make it new and different each year to keep ourselves interested. Just the creation of that event and setting up systems that had longevity was so exciting. It was exhausting, it was thrilling, it was wonderful.

Leading Organisations

MR: You’ve also been involved in organisations. I want to start with two ongoing organisations you’ve been a director of: Cycling Australia, now AusCycling, and the Amy Gillett Foundation.

Charlie: The Cycling Australia involvement came about through knowing Stephen Hodge at the Cycling Promotion Fund. Stephen had a competitive background and I don’t, I have a touring, advocacy background. I think it was recognised that the Board of Cycling Australia was an all-male – I won’t be too rude! – a patriarchal group with a focus only on competition. That was their background, that was their skill base, their knowledge, their experience. I went in there to perhaps help them see there was a greater world of cycling beyond just road and track, which was the focus at the time.

MR: How were you received, Charlie?

Charlie: One of the Presidents looked at me as I piped up in a meeting one time and he said, “It’s alright to have one Charlie Farren, but we wouldn’t want too many!”

I think that was the contribution I was able to make – to allow them to see what was going on around the world, because I would have been going to bike planning conferences in many different countries. I was interacting with a lot of different people. I was involved in advocacy within Australia, and I was involved with a recreational group that was Bicycle Victoria; the non-competitive side of cycling which, at that early stage, Cycling Australia wasn’t engaged with. It’s changed dramatically since then.

“The one vehicle that can still get from A to B in a given amount of time predictably is the bicycle. I think sometimes its bike envy that causes this rage.”

Through that involvement, I became a board member of the Amy Gillett Foundation (AGF). I can remember hearing about that accident. I was in France, in Lourdes, in a hotel. I was taking a group of cyclists during the Tour de France. I heard about that accident and, like everybody else, was absolutely devastated. As a child growing up in London, I was never allowed a bicycle because my father’s brother had been killed on a bike in London. He had gone under a truck. My parents would not countenance me having a bike or riding to school.

So the AGF, the aim of the foundation, really resonated. I truly believe in what the AGF is trying to achieve, which is basically safer cycling.

It’s that interaction between motorised transport and the vulnerable road user, the bike rider. That is an issue in Australia. It’s not the same in all countries of the world. In Europe, there is a much more forgiving road environment. But in Australia, I believe we have a very aggressive road environment, and we’re all contributors to that. Whether we are truck drivers, car drivers, bike riders, even pedestrians, we can get quite angry if our personal space is compromised. It works all the way down the chain.

The AGF is working to try and change those fundamental attitudes. It’s an enormous task, which I believe in strongly. We all have to have consideration for the people around us and on the roads as they become more and more congested. We’ve been led to believe the car will take us from A to B in a given amount of time, with no impediment, and that just doesn’t happen anymore. The congestion in the city means A to B could take any amount of time. Tempers are short, expectations are not being fulfilled.

The one vehicle that can still get from A to B in a given amount of time predictably is the bicycle. I think sometimes its bike envy that causes this rage. You see a vehicle that is still fulfilling that original proposition of predictability, enjoyment and, for the most part, reliability. All these other vehicles do not have that.

Bicycle Victoria

MR: Onto Bicycle Victoria, which I know wasn’t called that when you came on board. Now one of the world’s largest advocacy cycling organisations, and for your key role in that, made a life member of that organisation.

Charlie: Here I am, early days in Melbourne, involved with the Melbourne Bicycle Touring Club, having a lovely time, going out at the weekends, riding around the countryside, learning about Australia; but knowing that in the city it was uncomfortable to ride.

We did have within the Melbourne Bicycle Touring Club two people riding a tandem that were killed by a motorised vehicle.

There was an organisation called the Bicycle Institute of Victoria, and it was very much a one-man band. There was this dynamic guy called Alan Parker, who’d come from Britain where he had been involved with the campaign for nuclear disarmament. He also saw that conditions needed to be improved for bike riders. He was adamant, vociferous, he was forceful, but he was not terribly good at drawing other people in to help him. That was the pivotal role I played in those early days.

We knew that to achieve something would require more than one person, it would require more than Alan Parker. However hard he worked, however many tables he thumped on, we needed more.

Basically, there was a coup. The Melbourne Bicycle Touring Club backed me to stand against Alan as president, and I became president of the Bicycle Institute of Victoria which morphed into Bicycle Victoria. I was able to bring people in, to break that casing around one person and allow more people to come in. It was instrumental and set the scene for what happened subsequently, which was the growth of an organisation. We had a state bicycle committee in Victoria looking at the four Es: enforcement, encouragement, education, and goodness knows what the other one is.

We were running a little information service but we weren’t achieving much in advocacy. We didn’t have any money. They funded a financial plan, a business plan for the organisation, which clearly said: “Get your finances sorted, make money, invest in advocacy.”

That’s where the role of the Great Victorian Bike Ride was critical because that became a cash cow. It did that because hundreds of volunteers contributed their time. It was the efforts of the volunteers that allowed the organisation to retain some of the money to put into advocacy.

We grew from strength to strength. We thought the Great Victorian Bike Ride was pretty good. We thought we’ll do one in NSW, and Tasmania, and New Zealand. I even worked out one around Fiji, but we never did that.

MR: You still have more to do!

Charlie: Yes! It would work, because they’ve got footy ovals and you could do … anyway, we won’t go into that. It spawned lots of other rides. That one was meant to be the entry-level ride, the party ride, thousands of people. Timed for school groups to take part after their final exams. Entertainment, films at night, it was the party ride.

We had rides for families, Easter Bike, where you stayed in one place and the little kids could ride half a kilometer and feed the ducks. The teenage son could ride 200km with an Audax group. Everybody else had a plethora of different rides helped by the Melbourne Bicycle Touring Club, so that was the family ride. We had a one-day ride. We had this progression of rides that we hoped would launch people on their independent cycling voyage.

MR: You’ve still got a lot of life, there’s plenty of zest there. What sort of riding or other activities are still inspiring you?

Charlie: I’ve discovered that I go half as far in twice the time. I’m not so interested in doing the challenge rides but I think they still have a place. I’ve got a couple of rides that never came about. Even Around the Bay in a Day was always meant to be a closed route and that’s never transpired. People are now shoved off the freeway to go round these silly little back roads and there are endless different starting points. It’s not the iconic concept we had in the beginning.

I still want people to know how enjoyable cycling is. If you don’t ride, why not? It’s such an enjoyable way to move around. It would improve the atmosphere and decrease the pollution if a few more people did that.

I still enjoy telling people what to do and where to go. I do run a couple of small rides but I don’t I don’t regret leaving the frenetic, stressful 5,000-people-for-nine-days events behind. I’ve played my part on that stage. Other people can take that on.

The other thing we should have in Melbourne, which is probably not going to happen now, is a huge transport museum. We do not have a transport museum in Australia. We’ve got amazing collections like this one, car collections, motorcycles, but our history is predicated on transport. The government as yet hasn’t seen the light and put umpteen millions into the creation of a transport museum, but there is a little group of us that think that would be a good idea.

MR: Thank you very much for being an influencer.

Charlie: I haven’t been an influencer; I’ve only done what I wanted to do and enjoyed it. On your bike everybody.