The Tenuous Life of Temporary Infrastructure

Wollongong, NSW

Covid-19 has brought tragedy on a global scale, which I don’t want to disrespect in any way, but it has also brought unexpected opportunities.

Specifically, in relation to micromobility, we’ve seen ‘temporary’ infrastructure, literally popping up in cities all over the world. Over the coming months and years, the battles will be fought, city by city to either make permanent or discard each element of this new temporary infrastructure.

The language, ‘battles will be fought’ might sound too provocative and confrontational, but many of those trying to sway decisions in either direction would readily agree that it’s a fight for the hearts and minds of both the local residents and the key elected officials in each case.

The results are far from certain. Even in parts of ‘progressive’ London we’ve seen temporary infrastructure arbitrarily removed causing great controversy and heated debate.

But the following article will focus upon an example much closer to home.

My Local Case Study

Before going into any details about this case study, time for some personal disclosure. I intend for the Micromobility Report to always have an ‘Australia-wide’ perspective and not to be parochial in relation to any one city or state.

So it’s not without careful consideration that I’ve decided to write about a case study which is literally very close to home for me – about a 10 minute ride away to be exact.

I should also disclose that I volunteered for about seven years in a cycling advisory role on a Council initiated group that was originally called the Active Transport Reference Group. I resigned from this role a couple of years ago. During all of these years we lobbied for and made glacial progress towards seeing the case study I am going to discuss become a reality.

I live in the City of Wollongong, which is located on the NSW coast, 88 kilometres south of Sydney. After previous amalgamations, the entire city is part of a single local government. With a population of over 219,798 in 2020. This makes it the 22nd largest Council in Australia, when ranked by population.

In terms of transport infrastructure and urban form, Wollongong, like almost all Australian local government areas, is car-centric and sprawling.

But the case study project stands to benefit from several rare attributes of the city.

Firstly, it’s constrained within a long, thin triangle of land, with a row of mountains defining its long western boundary and sandy beaches facing the Pacific Ocean defining its eastern boundary.

There’s virtually no development, residential or commercial, allowed either on the mountain escarpment or on vast swathes of land beyond to the west or north for about 40 kilometres. This land is reserved for various state parks, water catchments and underground coal mines.

Therefore, land in central and northern Wollongong is scarce and expensive, often over a million dollars for a relatively small house block. As a result there’s been a boom in medium to high density residential development, particularly surrounding the case study’s route.

Secondly, an iconic piece of infrastructure was built by a ‘controversial’ former Mayor, Frank Arkell, way back in the 1970’s – a coastal shared path that runs for 30 kilometres within the Council’s boundaries from Thirroul in the north to Windang in the south, where it links with a further 5 kilometre stretch within the neighbouring City of Shellharbour.

Thanks to a combination of stunning coastal scenery, many coastal parks and reserves and a relatively flat route, this shared path is extremely popular for both recreational use and commuting.

But like almost every Australian infrastructure story of this nature, for 40 years there have been missing links, one of which is the grand-daddy of them all.

The actual city centre is not right on the coast, but a few blocks inland. Just to the west again is the quite heavily used commuter rail line, upon which frequent electric trains link the various suburbs of Wollongong to Sydney and beyond.

Just a short ride further west is city’s main sports complex, then the main TAFE campus and finally, tucked into the escarpment, the University of Wollongong which usually has over 32,000 enrolled students.

In transport planners’ terminology, these five features are all major ‘trip generators’. More specifically, when you think about universities, trains (that allow bikes to be carried) and sporting complexes, they’re huge potential cycling trip generators.

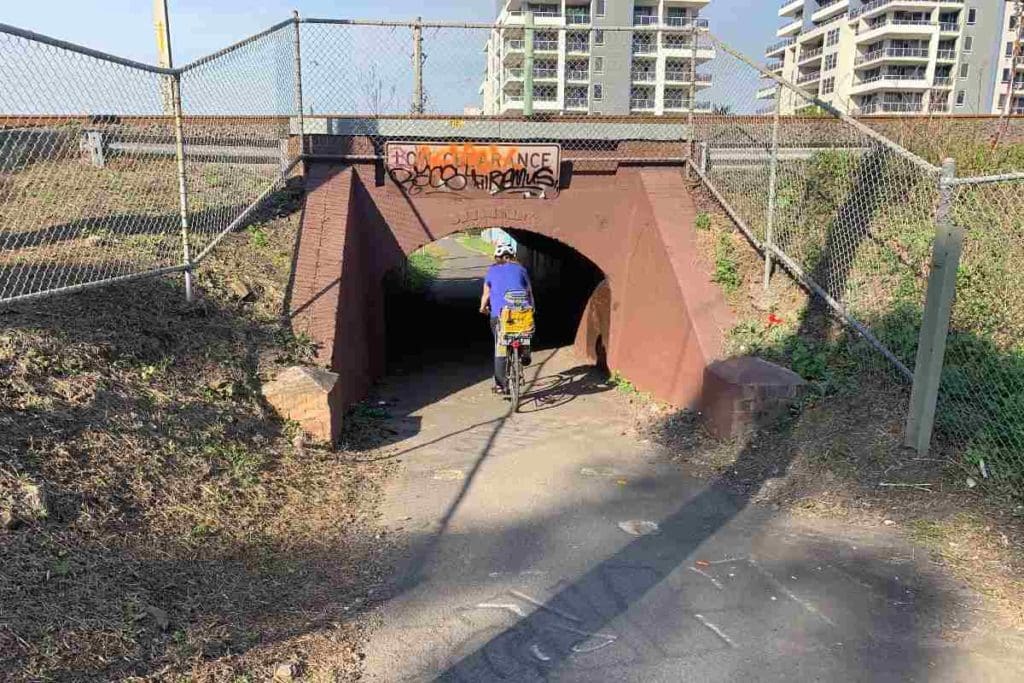

The railway line itself forms a barrier to cycling, because the relatively few road crossings are busy bottlenecks. But by accident of history, there’s an old underpass tunnel, which even through it does not meet current code in terms of its size, offers an invaluable cyclist and pedestrian crossing of this barrier.

There has been a mixture of separated and shared road infrastructure built from the western side of this tunnel to link the railway stations, sporting complex, TAFE and University, but on the eastern, city side of the tracks it abruptly stopped – until now.

There just happens to be a perfectly positioned east-west street, mainly flanked by residential apartments, that runs from the railway underpass tunnel almost all the way to the coastal shared path.

Smith Street runs parallel to Wollongong’s main shopping street and mall, Crown Street, and is just two blocks away to the north.

This has long been agreed upon as the perfect ‘missing link’ route. The plan included a short north/south ‘T’ section to link directly to the heart of the CBD shopping and business precinct. But despite a decade of campaigning, planning, even getting state government funding approved, nothing was built.

It was a history repeated countless times all over Australia. When one version of the plan involved the removal of car parking the local media had a field day. The usual irate vocal minority fired up and most elected Councillors ran for cover.

The plan that is finally being constructed and nearing completion at the time of writing, still required a smaller number of parking spaces to be removed, but thanks to the fact that it was a ‘temporary covid measure’ there was just enough momentum and political courage to see the first stage at least, finally get built.

According to a Council media spokesperson, “The works on Smith Street are part of a broader series of works around the Wollongong Local Government Area that form part of our endorsed Wollongong Cycling Strategy 2030, which was developed in consultation with the community. We will be asking for community feedback on the pop-up cycling project at various points over the next 12 months so we can determine what works best for our community.

Instead of recommending the obvious, safest, fastest route of allowing the cyclists to proceed straight through the intersection, they’re instead invited on an obstacle course, up an angled kerb ramp… Mind the power pole! Mind the pedestrians! Look out for vehicles backing out of the garages! Then cross at the pedestrian crossing with narrow kerb ramps, technically illegally unless you dismount and walk because there are no cycling lanterns fitted. However according to a Council media spokesperson, “Transport for NSW will be installing shared bicycle and pedestrian lanterns at a number of traffic signal intersections along the pop-up cycling routes throughout the Wollongong CBD.”

“Council conducted counts of cyclists, pedestrians and vehicles at various locations along the pop-up cycling route in the Wollongong CBD to establish a baseline for evaluation. There is a cyclist counter installed on Smith Street between Kembla Street and Corrimal Street that will remain at this location for the remainder of the trial. We’ll also do counts of vehicles and pedestrians separately.”

The spokesperson also confirmed that the north/south link that will T off the Smith St lane will be constructed immediately, running along Kembla St which in turn joins the eastern end of Crown Street Mall, the core shopping precinct.

You can see a Council media release about the project here and more detailed maps and plans here.

Good Decisions

As you can see from the photos that accompany this article, the result is a relatively wide, two way protected path. It’s 2.5 metres wide, plus buffer zones. The main protection comes in the form of parked cars, which now park about three metres towards the centre of the road from their original spot next to the kerb. The lightweight bollards and bolt-in plastic median strip, whilst not a perfect long term solution, form a bright, visible, clear barrier.

Now traffic along Smith Street has been reduced to one, one way lane. Most of the road is 40 feet wide in the old scale (12.192 metres), which was common a century ago when the grid was probably laid out. This is the same width as the famous Burke St in Sydney where they’ve managed to squeeze a two way protected path, two lanes of parking and a traffic lane in both directions, which is what I previously recommended for Smith Street, but it’s a very tight fit.

The one way, one traffic lane solution allows for a wider bike lanes, a wider buffer zone and a wider traffic lane. For a temporary solution it has a nice long term look and feel about it.

One particularly courageous decision (by Australia’s low standards) was to remove about half a dozen car parks on Harbour Street near Belmore Basin. This is a 100 metre final link between the eastern end of Smith Street and the coastal path. Because this stretch is right next to an extremely popular swimming, eating and general recreational precinct, parking here is in very high demand, especially during summer.

But this is also the final, critical stretch to link Smith St (this photo was taken on the corner of Smith St and Harbour St) and the iconic coastal shared path (which runs just in front of the large pine trees in at the end of this road.)

No doubt some of the well-heeled owners of expensive houses and apartments along this stretch have been voicing their opposition, but for now at least, the spaces have been replaced by a not quite completed final stretch of the path.

Bad Decisions

Unfortunately as often happens with Australian infrastructure, the intersection treatments are terrible!

I’m not sure whether this is due to the designers having brain fades, totally not listening to and understanding the desires of cyclists, or the councillors going weak at the knees. From past experience, I would imagine all are strong possibilities.

In particular, the design expects users to make abrupt deviations onto the footpath at several intersections, then cross at unmarked crossings. The facility was not quite finished and open for use when I took the accompanying photos, so perhaps there might be some safety markings and signage still to come, but the abrupt deviations are certainly intended.

You can just see a grey horizontal line in the middle distance behind the lights. This is the railway line under which there’s a cycling and pedestrian tunnel that is a critical link to the major trip generators beyond including the University of Wollongong.

The protected lane even swaps sides at Flinders St, the busiest intersection of the route.

It’s not yet fully clear, but it looks like cyclists are expected to dismount and walk across two pedestrian crossings, requiring two traffic light cycles to negotiate the intersection.

Currently, there’s no guidance for them whatsoever.

Any route is only as good as its weakest links. Through these design flaws The City of Wollongong is doing its best to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

Consequences

As a result of these poor intersection treatments, users are expected to take a slow, and ultimately more dangerous route. It’s difficult for beginner cyclists ‘8 to 80 years’, as this should be designed for, to cope with relatively steep, angled curb ramps whilst looking out for motor traffic in all directions.

If they choose instead to take the logical and safer option and ride straight through, because this has not been designed for, there’s no sensors at the signalised intersections to register a cyclist or other micro mobility vehicle waiting to cross. They will have to wait for a car to trigger the lights, which can be infrequent at some times of day.

At one intersection that has a roundabout the cyclists are expected to cross around the corner where the sight lines are terrible.

Apart from the immediate problems of navigating this inferior design. There’s a more ominous problem. Alack of perceived safety and amenity can lead to a lack of ridership. This can become a self-fulfilling prophecy for the nay-sayers, “Look, no-one’s using it!” Or perhaps, “Those arrogant, ungrateful cyclists aren’t using it properly!”

Inexperienced cyclists find it challenging to negotiate kerb ramps, look out for traffic, then do a sharp right hand turn when they cross to the narrow footpath opposite, to avoid the retaining wall.

Given that this project is only a trial, it needs to show usage just for its continued existence, let alone its improvement to a true world class facility.

After a decade of campaigning and previous inaction, to finally see some green shoots on the ground is heartening, but the Smith Street protected path’s existence is still tenuous at best.

Hi Phil,

I got a comment from Exsight Tandems the visually impaired cycling group that they find it too difficult to negotiate the sharp turns and kerb ramps at intersection with tandems and visually impaired stokers

This is an issue that was overlooked by council and also effects riders with trailers

You can find info on Exsight Tandems at https://exsight.org.au/

Regards

Werner