A Tale of Two Cities

Melbourne, Victoria

I’ve never actually lived in Melbourne. But over the past 31 years since starting Bicycling Australia, our first cycling media business, I’ve usually visited Melbourne, which is the centre of Australia’s bicycle industry, at least six times per year… once every eight weeks or so. That totals around 200 visits, so it’s a familiar city to me.

But like everyone else, covid changed all that. Because of lockdowns, interstate travel restrictions and the sheer risk of having to quarantine for 14 days if you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time, I’ve been staying at home. Therefore, a recent visit was my first chance in about 18 months to have a really good look around.

Just like the frog in the saucepan doesn’t notice the water gradually getting hotter, some Melbourne locals who I spoke to didn’t think too much had changed, but after such a long absence, to me, the changes were stark.

The divide between the inner city and outers suburbs has become much more apparent.

Two Cities in One

Like every city, Melbourne has been shaped by its history. From very humble beginnings in 1835, Melbourne grew modestly for its first 15 years until gold was discovered in Victoria and the great gold rush began in 1850. Over the next 40 years, Melbourne boomed to become the richest city, and second largest, in the then huge British Empire, only exceeded by London.

The boom peaked in 1888. Amazing suburbs full of grand houses and wide promenades were built. Then came the 1890’s depression and in the first decades of the 20th century, two world wars and the Great Depression of the 1930’s.

After World War II the car became king and there was a huge flight to the ever further sprawling outer suburbs. This proved to be a godsend for inner city Melbourne, because much of it was neglected and left un-touched.

Having been preserved by accident, some sectors of society began to realise their jewel and heritage protections gathered pace from the 1970’s. At the same time, young people, ‘hippies’ and other ‘progressives’ started moving back into what were then cheap, but increasingly desirable inner suburbs.

Melbourne was also the only Australian city that kept its extensive tram network. But this network has had relatively few extensions over the past 100 years, so trams still mainly serve the city and inner suburbs.

Melbourne Today

Fast forward to 2021 and Melbourne now has a population approaching five million. It’s surrounded by a vast, still-sprawling outer ring, with some suburbs now being built 50 kilometres from the city centre.

But Melbourne also has by far the largest, best preserved ‘pre-car’ urban core of any city in Australia.

By ‘pre-car’ I mean that, because these suburbs were all designed and largely constructed prior to 1890, they pre dated motor vehicles, which did not become commonplace in Australia until the early 1900’s. Therefore these inner suburbs were not designed around the needs of privately owned motor cars, unlike the car-centric outer suburbs.

Therefore, they have a host of attributes that make them more amenable to cycling and other forms of active transportation and micromobility. These include:

- A rectangular grid street pattern

- Many quiet back lanes, originally for the ‘night cart’

- Whole suburbs full of houses with no driveways at the front and little off-street parking

- A much higher population density compared to post-war outer suburbs

- All essential services within human scale distances including shops, parks and recreational facilities.

- A dense overlay of public transport with train and tram stops within easy walking or cycling distance.

- Traditional ‘shopping strips’ and some vibrant old style markets dominating the retail landscape, rather than the car-centric shopping centres of the outer suburbs.

Most of Melbourne is also quite flat and the weather, although famously changeable and cooler than more northerly Australian cities, is still mild and snow-free throughout winter.

All of this laid the foundation for a fantastic cycling city.

But two key obstacles still needed to be tackled – massive, relentless volumes of motor vehicle traffic including commuters from outer suburbs either passing through or driving to the CBD and inner city, and consequential demand for huge areas of car parking in the CBD and inner city.

These and other obstacles have been tackled in what has so far been a 50 year struggle for the cycling advocacy movement. But this movement has gradually grown in size and picked up allies along the way.

Climate change and covid have blown strong tail winds and accelerated progress. Although Melbourne is certainly no Copenhagen or Amsterdam, inner city Melbourne at least, has without any doubt the strongest cycling culture of any major Australian city.

It’s another ‘trial’ but as this photo and video link demonstrate, it’s working well.

City Centre & Inner Suburbs Landscape Today

There is a huge amount of development happening in both the CBD and inner suburbs right now and much more that has only recently been completed.

In the city, new skyscrapers are dominating the skyline. Many Melbournians are concerned about the ‘Manhattanisation’ of their city. And not without reason. The tallest residential tower called Australia 108, is 100 floors high, giving it the most floors of any building in the southern hemisphere.

Below it stretches a long list of residential buildings in particular with 50 or more floors.

As you can see from the photos that accompany this article, the Southbank precinct in particular where many of these super-large buildings are located, has become quite a sterile concrete jungle with wide, car-dominated streets.

But moving out from the CBD to the next ring, the new development is on a more human scale of medium to high density, mixed retail, commercial and residential development, mainly on tram corridors.

These old, inner city suburbs are really the ‘Goldilocks zone’ when it comes to urban cycling in Melbourne. The City of Yarra which encompasses the inner northern and eastern suburbs, is arguably the most progressive of the inner city local government areas, although some others, including the City of Melbourne itself, are making progress towards catching up.

In these jurisdictions here are some of the features that are making cycling more accessible for a wider cross section of the population:

- Lower speed limits. 40 kph has become the norm for the inner city, but there are quite extensive 30 kph ‘trials’ in some parts, which should become permanent.

- Protected bike lanes are becoming more common. In many cases, streets have graduated from having nothing to a painted lane and now to a protected lane.

- Advance stop boxes or ‘bike boxes’ have become commonplace. These work very effectively at signalised intersections where there are also separate bike ‘lanterns’ that turn green about five seconds in advance of the main lights turning green.

- ‘Bike streets’ where there are two dashed lines down the sides of the road suggesting that cars should use the centre section. This is a common, successful solution for low speed, low traffic volume streets in the Netherlands, but quite new to Australia.

- Melbourne’s first ‘Dutch style’ intersection (see photos and video above) appears to be working well. You can see a previous article we wrote about this intersection here.

- Many one way streets with ‘Bicycles Excepted’ signs allowing cyclists to ride against the flow of traffic. Once again, this treatment is safest in low speed, low volume streets.

- Reclaimed on-street car parking spaces for ‘parklets’ and outdoor dining space for café’s

- Traffic calming measures including speed bumps, pinch points, lane and street closures to prevent ‘rat runs’ (where motorists try to avoid using the main roads).

- Due to historic precedents, there is a far more intertwined mix of residential, commercial and retail activities than in the more ‘monoculture zoned’ outer suburbs. This leads to shorter travel distances to work, education, shopping and other trip generators, making cycling a more attractive alternative to driving.

All of these measures have combined to help foster a bike culture. Every day, in all weathers, you’ll see people riding bikes everywhere in the inner city. This in turn builds ‘safety in numbers’ and ‘social acceptance’ and so the virtuous spiral continues to ascend.

Outer Suburbs

Step beyond these inner suburbs and the landscape quickly transforms into the same post-war suburbia that you see in every other Australian city.

The outer suburban landscape is dominated by wide, fast main roads, many with 80 kph speed limits and little cycling or public transport infrastructure

As a result, you see relatively few cyclists braving the huge amounts of traffic.

Thanks to Melbourne’s abundance of flat surrounding land, as you travel further away from the CBD you find ever more suburban sprawl across the vast plains.

Although there are now some ‘bike friendly’ regulations in place for developers of new subdivisions, when you’re 40 kilometres out, in a low density urban environment where over 90% of trips are done by motor vehicles, you’re pedalling into strong headwinds.

There are some nice trails along various creeks, rivers and other linear parks, but often these stop at six or eight lane barriers in the form of high speed main roads, that deter many potential users.

How Will This Tale End?

It seems to me that Melbourne has become two cities, the inner and the outer, with the differences between them becoming more stark, not less.

Census data shows that the commuting journey ‘mode share’ for cycling in Melbourne’s most cycling hostile outer suburbs is only about 1%, compared up to 14% in the inner suburbs. That’s more than a 10 fold difference.

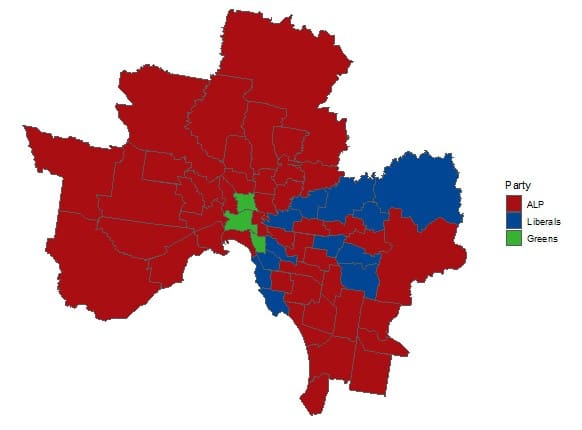

Voting patterns are also starkly divided by geographic region in both local council and state parliamentary elections. This tends to suggest that the more ‘progressive’ areas will accelerate their adoption and fostering of all forms of micromobility while the more ‘conservative’ areas will fall further behind.

Will this develop into tribalism like we see in USA with entrenched ‘red areas’ and ‘blue areas’ and even antagonism between the two?

Will the inner city inspire the outer, or will the outer city try to protect, regulate and take whatever steps it can to build a moat and stop inner city ideas invading its territory?

Join the Conversation:

What do you think are the answers to these questions. What does the future hold for the inner vs outer city divide?