Active Transportation Lessons from London for Australia

London, UK

Recently I spent a week in London enjoying glorious mid-summer sunshine and 9:30 pm sunsets while my colleagues in Australia were enjoying a record mid-winter cold snap. Ahh… that felt good to write!

But it wasn’t all beer and skittles, as they say in the UK. Back in March when I made my annual pilgrimage to the Taipei Cycle show, I wrote this article entitled Active Transport Lessons from Taipei for Australia. It’s a long, detailed article that’s been very well read with some positive comments. So before heading to London I’d already planned to write a similar article and made sure that I used every form of transport while I was there.

A Different Environment

In Australia we have fewer people, more land and less cycling infrastructure in our cities. We have more recreational and sporting mountain biking, road cycling, gravel riding, but less cycling for transport.

By contrast, London packs nine million people into relatively small space, with a further 10 to 20 million people, depending upon where you chose to draw the line, living within a close enough radius to commute each day into London to work. That’s enabled by a vast spiderweb of regional rail lines, radiating out from central London in every direction, plus of course, a road network.

In total, you have the equivalent of Australia’s entire population living in an area that’s significantly smaller than our smallest state, Tasmania.

In central London and its surrounding inner suburbs, most people live in apartments that were built before the automobile era, with no garages or off street parking and most have scarce nearby on street parking.

Added to that, central London has a daily congestion charge of £15 (A$30) that applies if you drive for even one minute within a large central area, unless you live within the zone and have a local resident’s exemption.

There’s also a larger ULEZ (Ultra Low Emissions Zone) in which any vehicle that does not meet strict emissions standards pays a further tax. Then there are LTN’s (Low Traffic Neighbourhoods) in which cars are blocked from certain roads while bikes are allowed to pass. Add to that 20 mph (30 kph) speed limits on most roads, extensive but expensive public transport and a much more advanced network of protected cycling routes.

All of these factors combine to make London a city where there’s relatively less car traffic and way more cycling happening for everyday activities than you see in any Australian city – even though the weather there is colder and wetter than most of Australia’s.

Bike and Scooter Share Schemes

London’s original bicycle share scheme is now called Santander Cycles, named after the naming rights sponsor, which is a bank. But informally, they’re commonly called “Boris Bikes” after regular cyclist Boris Johnson, who was Mayor of London when the scheme was introduced before later becoming Prime Minister of the UK.

Unlike schemes in Australia and the USA which are mainly privately owned and operated, Santander Cycles is owned by Transport for London.

This bikes and docking stations are provided by 8D Technologies, a Canadian company that also supplies systems for many other cities.

As of 2024 there were 12,000 bicycles operating on a docked system with 800 docking stations that stretches approximately 15 kilometres from east to west and eight kilometres from north to south with an area of about 100 square kilometres. This makes it one of the world’s largest docked bike share systems.

Having been founded in 2010, it’s also one of the first bike share systems. Initially all analogue bikes, electric bikes have been introduced from 2022. Like most schemes worldwide, e-bikes are far more popular and riders are willing to pay the higher fees that are charged for e-bikes. Santander have expanded the fleet to about 2,000 e-bikes but this still only accounts for one in six of the total fleet.

Santander peaked at about 11.5 million rides in 2022, but is now facing increasingly stiff competition from the dockless e-bike and e-scooter schemes of private operators. The largest of these is Lime, which is estimated to have recently overtaken Santander with the biggest fleet in London.

Other London operators with either smaller fleets or smaller areas are Human Forest, and Dott / Tier who merged in March 2024. All of Santander’s competitors offer dockless systems and some offer e-scooters as well as e-bikes.

I mainly rode Lime dockless e-bikes, but also tried a Santander docked analogue bike. The Lime bikes are only single speed with a relatively high gear ratio, but have a powerful motor with plenty of torque, so it’s enough to get up any of London’s gentle hills.

What disappointed me most was the poor state of repair of the shared fleets, Lime bikes in particular. On one morning I had to try four different bikes before finally finding one in good repair. Many of the bikes were grubby and battered. Why can’t Lime keep their fleet in better condition? They certainly charge enough, particularly if you just do a casual hire. I found the one and three hour hire packages to offer much better value.

The Santander bikes were dirt cheap by comparison, but I certainly noticed the lack of e-power assistance.

Cycling & Scooting First-Hand Experience

It had been about 12 years since I last rode in London. Back then we were publishing a series of cycling guidebooks including “Where to Ride London” and I rode many of the best cycling routes of that era with our local author Nick Woodford.

I’d seen and read quite a lot since then about the new cycling infrastructure that had been build including the “Cycling Superhighway” network. This description was initially flattering for some narrow second class “paint on roads” cycle paths. But more recently, most of this network has been upgraded to protected cycle lanes.

When I set out for my first ride from our accommodation in Canary Wharf to the Houses of Parliament, I expected to encounter a lot of vehicle traffic, but within a block I was on “CS3” (Cycle Superhighway 3) and enjoyed protected cycleway all the way for a trip that was faster than any other means of transportation.

Two of the best paths I rode were the along The Embankment and along the southern boundary of Hyde Park. They were wide, smooth, fully protected and extremely heavily used.

I also saw many cargo bikes of all shapes and sizes, two, three and four wheeled. These were mainly being used for deliveries but also for local government services such as street maintenance and gardening.

Overall, London has improved enormously over the past 12 years – but Paris, which I rode around later during the same trip, has improved more! Time for Australian politicians to take notice…

Walking and Footpaths

Walking has the biggest mode share in the centre of London. Most of the footpaths are well paved, but they can be very busy in places.

It’s a pretty sad indictment of the city’s priorities to see that one of the busiest streets of all, the famous department store precinct of Oxford Street, still has pedestrians crammed onto the footpaths, while vehicle traffic uses most the road space. This stretch should be a pedestrian mall rather than the stressful walking experience it currently is.

At most city centre intersections, you don’t have to press a “beg button” to get a walk signal from the traffic lights. The lights give walk cycles quite frequently. There are also a lot of traditional striped pedestrian crossings, which most motorists honour.

London Underground

London’s famous Underground was the first in the world, dating back to 1863. It’s no longer the largest system or the busiest – they’re mainly in Asia. In fact, it’s not even in the top 10 by any metric. But it’s still far larger than any Australian’s city’s rail system

Up to five million passengers per day are transported on 619 trains over 11 lines that stop at 272 stations. There are 350 lifts and 573 escalators, but I was both surprised and disappointed to find that many of the older stations still don’t have any lift or even escalator access to their platforms. This includes some busy, central city stations.

London’s underground is showing signs of chronic underfunding. The trains are up to 52 years old. Most are not air conditioned and can be noisy, hot and crowded. The old lines are small, with narrow trains and narrow platforms.

What was once state of the art is now completely outdated compared to modern systems. Due to its crowding and space constraints, it’s quite understandable that bicycles are not allowed on most underground trains, particularly during rush hour. An exception is made for small folding bikes such as Bromptons.

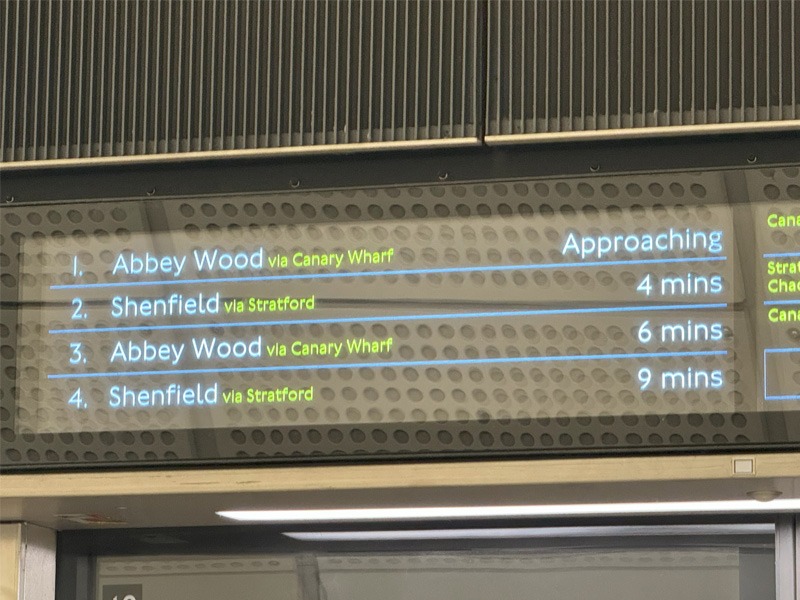

By contrast the brand new Elizabeth Line is equal to anything worldwide and shows what’s possible if serious investment is made.

London Overground

This is a suburban rail network, which as the name suggests, mainly runs on above ground tracks, but also in tunnels. Ironically at one point an Overground line actually tunnels underneath an Underground line.

We rode a few Overground trains and they were on time, reasonably clean and modern – about the same standard as most of Australia’s suburban rail networks.

But once again, we came across multiple suburban stations including very busy ones, with only stair access to the platforms and the stations in general were fairly old and tired.

Light Rail

London has fairly extensive light rail networks, the largest and oldest being the Docklands Light Railway (DLR), first opened in 1987 and extended multiple times since. It uses driverless trains.

London’s system categorises the DLR as a separate entity to London Trams, which are vehicles with drivers that run on a mixture of public roads and separate rights of way including some former rail line routes. Trams operate in suburban areas.

Buses

London’s red double decker buses are possibly more famous than the Underground. It has more ridership than the Underground at over 2 billion passengers per year (5.5 million per day) with a fleet of over 8,000 buses. 95% of Londoners live within 400 metres of a bus stop.

Even relatively quiet routes such as the one stopping outside our accommodation had a good frequency of service.

London is gradually electrifying its fleet, with all new buses from 2021 being zero emission and about half the fleet being fully electric or hybrid by 2024, a task that was completed by Chinese cities years ago, but barely started in Australia.

London plans to pass 2,000 fully electric buses by 2025.

Motor Vehicles

London was the world’s second city (after Singapore) to introduce a congestion charge for driving into the city centre. The current congestion charge is £15 (A$30) for driving inside the zone between 7am and 6pm on a week day or noon and 6pm on weekends and public holidays.

The congestion zone is roughly a circle of about five kilometres in diameter and 21 square kilometres in area, that covers the city centre.

This system has worked as intended to reduce the volume of vehicle traffic and air pollution levels in the city centre.

In 2019 London also introduced an Ultra Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ). This has been expanded since then to include all of Greater London. The charge only applies to mainly older vehicles that don’t meet certain emissions standards. It uses cameras and number plate recognition to administer the charges.

Under its current standards ULEZ is not a system to specifically encourage electric vehicles as over 90% of internal combustion engine vehicles comply with the current requirements.

The third main system designed to reduce motor vehicle traffic in London is Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTN). These mainly rely on modal filters (where cyclists and other micromobility rider can pass through barriers but motor vehicles cannot). These areas are sometimes called mini-Hollands.

There are now dozens of LTN’s across Greater London and one study showed the health benefits alone had a financial value 100 times higher than implementation costs.

Fuel is also more highly taxed in the UK with the typical price of petrol and diesel during my visit around £1.50 (A$3.00) per litre.

London’s “traditional” black taxis are now mainly modern replicas of the old design, but with wheelchair access and in many cases, fully electric powered. There are also many Uber vehicles that are cheaper than traditional taxi fares, but still relatively expensive compared to other cities.

Ferries

Although there are passenger ferry services along the River Thames, they are privately owned, relatively expensive, and seem to be mainly geared towards tourists. They’re a great way to see the city on a clear day and bikes are allowed on the ferries.

Inside Transport for London’s Nerve Centre

Most of London’s transport network is owned and operated by single government authority, Transport for London (TFL), which was established in 2000 after consolidating various separate organisations.

TFL is responsible for the Underground and Overground trains, Light Rail, Trams, Buses and docked bike share.

TFL has almost 30,000 staff and derives half of its total income from fares, which is a far higher proportion than is the case for Australian public transport systems.

I was very fortunate to have been invited by the outgoing Chief Operating Officer for Transport for London, Glynn Barton, to have a guided tour of their operational headquarters, which is housed in a large, high security building, just across the Thames from the city centre. I was not allowed to take photos within what is understandably a high security facility.

Within the centre there are two main control rooms, one overseeing the London Underground and the other the road network including a side area that manages 12 tunnels.

From the road centre they can control 6,500 sets of traffic lights, both to minimise delays to the daily traffic flow and also manage emergencies, such as giving green light access to emergency vehicles.

At the LUCC (London Underground Control Centre) continuity of service is also a top priority. There are thousands of ESUB’s (Electronic Status Update Boards) throughout the network that show each of the lines and whether there is a “Good Service” or delays.

My host, Steve Manuel, said they’ve learned over the years that giving passengers accurate and timely information is critical.

For example, if a train is stopped between stations in a hot tunnel, they don’t want passengers panicking and walking along the tunnel. “Otherwise the power has to be shut down and you lose control of your network,” he explained.

He said the number one cause of delays was “asset failures”, meaning trains, signals and other equipment malfunctioning.

Steve detailed a host of other challenges including different trains being used on different lines and drivers only being certified to operate on certain lines and not others, resulting in more challenging juggling of rosters and availability.

There’s also the stress of “jumpers” – people who commit suicide by deliberately jumping from a platform in front of an arriving train. The newest stations have PSD’s (Platform Screen Doors) that eliminate this risk, but the vast majority of stations do not have these.

Conclusions

It’s little wonder that there’s so much cycling and walking activity in London. Although private e-scooters are officially illegal, I also saw quite a few of them being ridden.

London has the high urban density that favours micromobility. Plus, public transport is expensive. Private car driving has been deliberately made even more expensive through government policies.

Cycling all looked wonderful when visiting in mid-summer, but the reality for about six months of the year would be often commuting to work or elsewhere in cold, wet and dark conditions.

If you’re a regular London resident on a tight budget then it’s still easy to see why cycling is such an attractive option when it comes to speed, convenience and overall low cost.

This is great Phil, thanks! As you say, London has gone hard on the sticks to discourage car use with 4 big policies – congestion charging, ULEZ, LTNs and 20mph (almost) everywhere. All these feel a million years away from being implemented here in Sydney. So we continue to tinker at the edges of achieving much-needed mode shift.

gooood site thanks a lot

Brilliant article!

Great summary article Phil. Did you make it out to Waltham Forest in north-east London ? A great example of an outer Borough that has delivered transformational change in the last 10 years which if copied elsewhere would dramatically change London for the better !

Hi Andy, sorry to say that I didn’t make it out to Waltham Forest but I have heard about it as being a pioneering example of better traffic management / liveable urban design.