It’s Time to Revise the Regulatory Framework for Light Electric Vehicles

Melbourne, Victoria

The revolution in electric micromobility has presented a range of challenges for regulators and enforcement agencies. The status quo, which had existed for many years, in terms of the range of mobility options needing to be regulated and enforced, has been disrupted by the emergence of electric kick scooters and a variety of other electric personal mobility devices.

Regulatory frameworks here in Australia, as well as in many other jurisdictions, never envisioned the rapid developments in technology generated by the lithium revolution. Particularly problematic is the regulatory straightjacket worn by many regulators which focuses on power as a primary characteristic for regulatory control – specifically the 250-watt limit first applied to e-bikes. In a crash, it is the dissipation of kinetic energy (mass times speed squared) which creates adverse safety outcomes, particularly where it is the human body that dissipates that energy.

Speed rather than power is far more important in determining both the risks to be managed and the competitiveness of the mode as an urban transport option. Operating speed should be the focus of light electric vehicle regulations, just as it is for motor vehicles. However, there has been concern that some micromobility devices are capable of speeds far above the speeds limits for those devices.

I suspect that every motor car offered for sale in Australia is capable of operating at speeds well in excess of all State maximum speeds. I don’t hear calls to mandate the maximum speed that vehicles can attain. To my knowledge, only Volvo has acted unilaterally to restrict the maximum speed of their vehicles to 180 kph but that speed is still in excess of all upper speed limits in Australia.

While much reliance is placed on having nationally consistent rules and regulations, the shortcoming of that approach is the lowest common denominator, or most recalcitrant State, dictates the outcome.

Thankfully that has been overcome by some States breaking from the pack and having the courage to develop regulatory initiatives which better suit the situation they face on the ground. Personally, I take heart from:

- Queensland removing power from its regulations for e-scooters and placing emphasis on operating speed.

- NSW increasing the power limit on cargo bikes to 500 watts and reports that Tasmania is considering a similar move

While the merits of that particular magnitude increase in power limit are debatable, at least there is some recognition that limiting light electric cargo vehicles to 250 watts means forcing operators to look for flat or downhill routes when their vehicles are loaded.

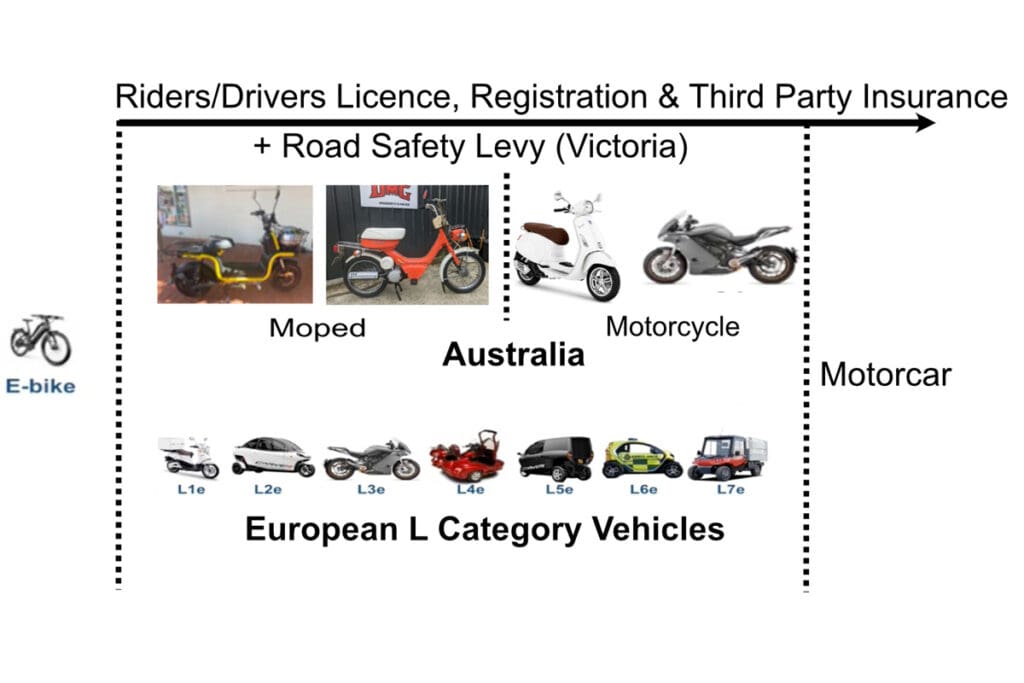

Australia’s current regulatory framework is too coarse to be capable of responding to the opportunities presented by light electric vehicles. Figure 1 compares the three-category Australian system (e-bikes, motor cycles/scooters cycles and motor cars) with the finer-grain classification provided by the European L category. At the very least, specification of a Light Electric Freight Vehicle (cargo bicycle category) would allow for regulations that would facilitate the effective use of those vehicles in urban freight operations in Australia.

Any set of regulations will require enforcement and that includes enforcement of operating speeds for micromobility devices operating on bike paths, shared paths and footpaths. That is happening in Queensland, consistent with its regulations.

There are micromobility devices offered for sale in Australia which are clearly capable of high speeds (50-100kmh). When ridden legally, they don’t require the rider to be licensed or the vehicle to be registered or covered by compulsory third party insurance. How then should we ‘manage’ irresponsible use of those micromobility devices when they are ridden at speeds in excess of speed limits?

In that case, their performance is more clearly aligned with the mopeds and motorcycles category.

One option would be to sharpen the sting associated with enforcement so that when a rider is found to be operating a micromobility device, powered solely by an electric motor (such as an e-scooter), above the speed limit, they would not only be penalised for exceeding the speed limit but also for being unlicensed and riding an unregistered and uninsured vehicle.

Light electric vehicles and micromobility devices present new opportunities to broaden the mix of urban transport options and enhance the sustainability and liveability of urban areas. There will be an ongoing need to manage the balance of risk and opportunity, but regulatory change is needed to unlock their potential.

Professor Geoff Rose

Monash Institute of Transport Studies

Monash University