Opening the Floodgates to Highlight Imbalance Endangering Cyclists

Ontario, Canada

Canadian Tom Flood made a huge impact with his presentation at last month’s Micromobility Conference & Expo in Sydney.

The man behind the powerful messages and images is revealed in this issue of our influencers! transcripts, as we continue to look back at Series 1 of the influencers! podcast series.

Tom worked in the advertising industry and spent much of his career creating campaigns for the auto industry, even though he was commuting to work on a bicycle and facing a hostile environment caused by the very products he was helping to sell.

His epiphany occurred when he tried to ride with his young boys to preschool and suddenly realised our society has been perpetuating a myth that cars are always a good thing for cities and families.

Tom began using his considerable talents to create impactful images and videos to tell a completely different story.

Micromobility Report: Tell us a bit about Hamilton, Ontario. How long have you lived there? Describe the city and the cycling scene there.

Tom Flood: We moved here about seven years ago. We lived in Toronto for many years and wanted a different pace of life, so decided to move 45 minutes down the road from Toronto to the west in Hamilton, which is about a half a million people now, an urban centre. It’s been a really great place for us. We do a lot of cycling here: a lot of cycling kids to school, walking to school with our kids. There’s a lot of change going on in Hamilton over the last 20 years now.

“I’m really just trying to highlight the imbalance present every day for every single person that is outside of a car.”

MR: You’ve earned a worldwide reputation in cycling media through your work, which I would describe as insightful and creatively brilliant. How would you describe your work?

Tom: The best description I would give the work I’ve been doing in the cycling advocacy space really comes down to trying to highlight the absurdity that’s on our streets. That’s the biggest driver for me and what pushed me into this space.

It was seeing the complete imbalance on our streets. I’m really just trying to highlight the imbalance present every day for every single person that is outside of a car, and to open people’s eyes.

“I would be cycling to work in Toronto every day, battling the dangers and the drivers getting to work and then spending 10 to 12 hours a day developing content that perpetuates the culture that was endangering me on the way in and out of work.”

MR: We are going to look at some still images and videos, but how would you describe them?

Tom: I come from the advertising world. There’s never really any intention specifically, but I think some of them are set up to mimic advertising and using some of the same tricks and tools I honed in my career.

MR: You weren’t always doing cycling work. Can you just describe the moment that changed the course of your career?

Tom: I worked on auto accounts for many years, doing corporate branding and storytelling for the auto industry. It was very strange because I would be cycling to work in Toronto every day, battling the dangers and the drivers getting to work and then spending 10 to 12 hours a day developing content that perpetuates the culture that was endangering me on the way in and out of work.

The awakening came the first time I took my kids to daycare and school on their bikes. It was an immediate light bulb moment.

I could not believe it, seeing it through their perspective. I don’t know how I missed it for so, so long. Seeing it through a more vulnerable road user’s eyes and through their perspective just changed everything for me, and once you see it, you can’t unsee it, and it’s hard to step away from it.

MR: You’ve had tertiary training and a long professional career with your own creative advertising agency. How important has all this experience and work been in the current body of work you’re creating?

Tom: I think it’s been very helpful. I’ve never intentionally set out to do this or utilise those skills and tools I learnt. It has been important but I think the bigger thing is once people have their eyes opened and see that imbalance, it’s about digging into the story that’s on our streets. That comes somewhat naturally to me but there’s stories that all of us can tell. It’s just a matter of finding the right notes to strike.

MR: I showed your work to my wife and she was moved to tears by some of the pieces.

The first one we’ll look at is Barriers. Sometimes the best way to remove barriers is to add one. How did you come up with that?

Tom: That picture was taken on a random trip in Toronto one day. I was just trying to snap some shots of some nice concrete barriers I was hoping we could implement where we are in our city. There was no intention for that to be anything other than a reference for me at a different point.

I flipped through my phone and saw that, and it just had the right look and the right feel. It’s a very traditional type of advertisement, an out-of-home print style ad, with a large image, large type, and a play on a flipped phrase for the headline.

MR: Is it coincidence there’s a Tesla in the background – an electric car.

Tom: It’s complete coincidence.

MR: It is serendipitous, isn’t it? There’s a whole issue there about electric cars being the savior of cities. We don’t have to do anything else. But as you would know, and many others in the active transport micromobility space know, that’s not the answer in its entirety at all.

Tom: That’s for sure. There’s obviously a large role for that but not the full answer.

MR: Let’s move on to Bell. The caption says: “There will never be a bell loud enough, a helmet strong enough, or clothing bright enough to make up for poor infrastructure.” You wrote that?

Tom: Yes. That’s my child in front of me and that’s going to school in Grade 1. I documented many of our rides as we’d go to school. That was still on the periphery of me taking a further step into building out creative pieces to tell stories. That was more of just a snapshot for me to show our councilors and things like that locally.

It was a very powerful image and truly shows the imbalance and absurdity that’s on our streets – and what we ask our children to do to go to school. It reinforces how we just put the messaging and all effort into the wrong space.

We preach safety for everybody outside the car so everybody inside the car can be dangerous – that’s the bottom line. We hear a lot about bells, we hear a lot about high visibility, so I wanted to wrap that up into a nice little statement that would, hopefully, resonate with lots of people.

It shouldn’t be a divisive or politicised topic. It is, but it really shouldn’t be. If we want to reach across that island and connect with other people, using the vulnerability of a child – not in a save-the-children type of manner but in a way that is as simple as the joy of biking to school – is something we should be able to relate to.

When you see the image of the child next to a large truck with a line of paint, and then you hear those words of our city leaders and police telling them “Put a bell on. Where’s your helmet, kid?” – it’s absolutely ludicrous. It highlights some of the absurdity on our streets and sitting in our council chambers.

MR: A few of the elements that make that image more powerful; your son seems to be leaning over in fright. Was that just another coincidence or the moment? Also, the crack there on the road, was that deliberate?

Tom: Not at all. These were very random. It was just a shot of us going to school and me happening to be with my camera riding right behind them. That image really sticks with me because it represents a very specific time in my journey with my kids.

MR: Was the truck parked or was it moving?

Tom: It was moving very slowly. It’s a residential street. Again, that just speaks to the situation and where we place value – what we prioritise.

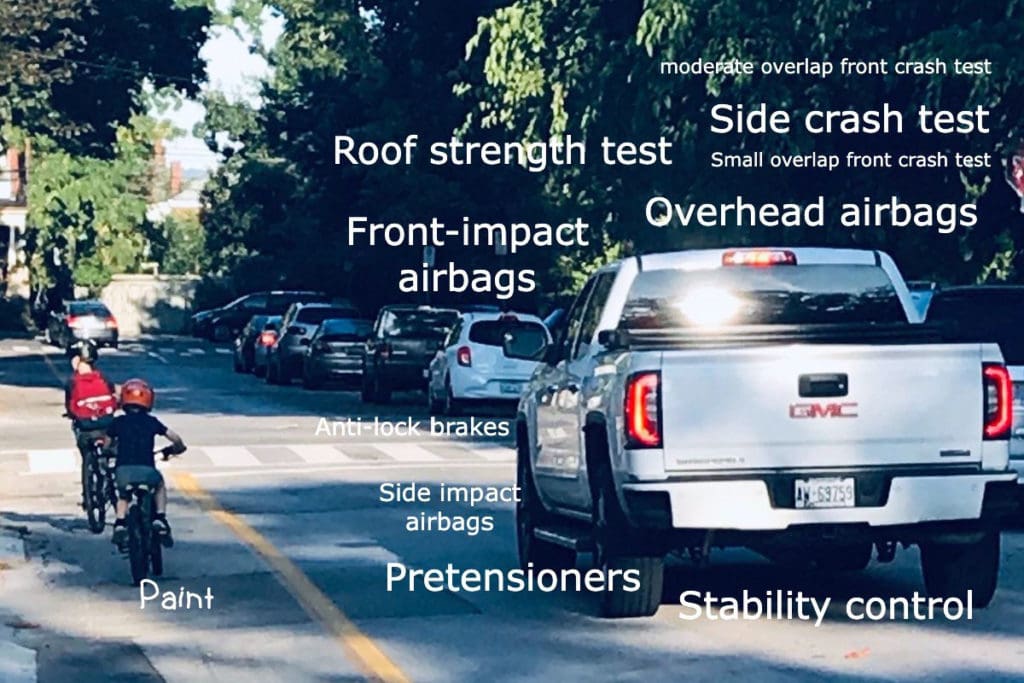

MR: Let’s move on to the next one, the trucks and bikes. You’ve got the pickup truck with all the features written around it, and then you’ve got both of your sons?

Tom: Again, that was just me taking a picture of them going to school. I was going to ride with them and they yelled back at me: “Dad, can you pretend you’re not with us.” They started riding away. I was like, “Oh, geez, I already hit that age”. They were so young. I snapped that picture to tell my partner: “Hey, they’re already telling me not to ride with them. I can’t believe they’re teenagers already.”

When I looked at the shot later, it’s just that striking imbalance. This time, the point is to highlight where we prioritise and play safety. It’s absurd what we do to protect everybody that’s inside a vehicle versus everybody outside the vehicle – what we consider standard safety for a car and what we consider standard safety for a bicycle.

MR: I think it’s inspired the font you’ve used for the word ‘paint’, like a young child’s handwriting.

Also, you clearly know how to use contrast as a powerful effect in your still images and videos.

Tom: It stems directly from the stark contrast on our streets every single day.

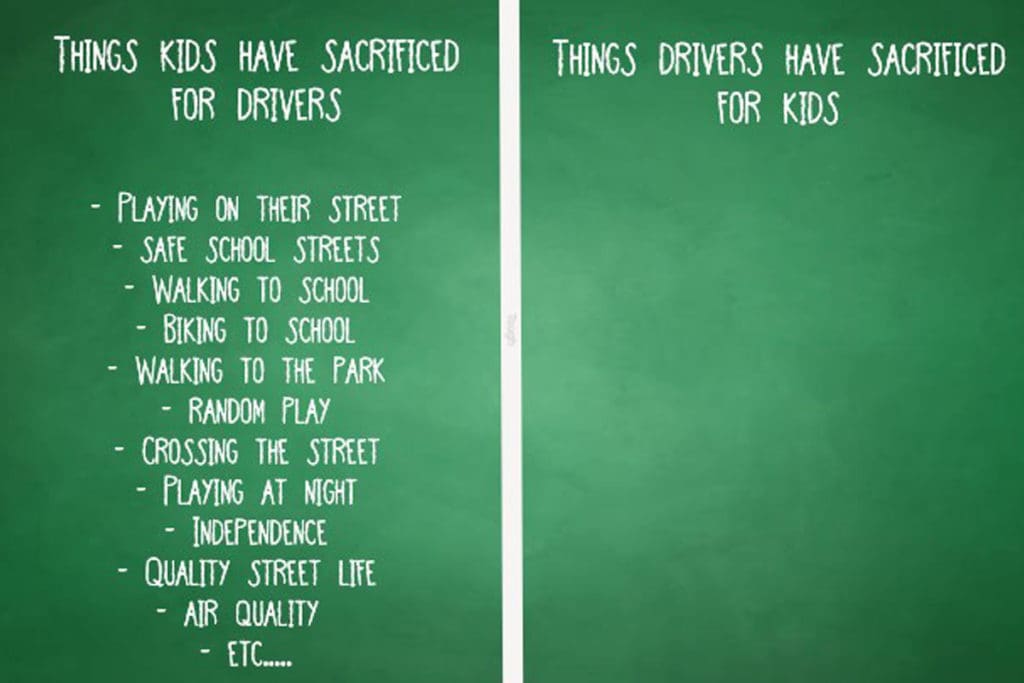

MR: We’ll move onto another one that uses contrast. We all make sacrifices. What was the inspiration behind that image?

Tom: That was very intentional. I took a picture of both my kids sitting on the kerb just outside our home here. They were just waiting and waiting for cars to pass, so they can go play, which is nothing out of the ordinary. That’s what kids do. It was just heartbreaking because it was taking so long for them to get that moment of joy to play on their streets.

I remember thinking: “We should all really give these kids a pat on the back for letting us have a go in our cars all day long. We should probably pin some medals on these kids because they’ve given up everything for us just to speed around.” I thought I would highlight what the kids have sacrificed for us and what we, in turn, as drivers, have sacrificed for them, which is absolutely nothing.

I thought placing it on a chalkboard would highlight the school-age idea and content behind it.

No one’s asked me that before, and I’ve never actually mentioned where that came from.

MR: I’m honored because you have attracted a lot of media, even in Australia.

We’re going to roll on to five videos and start with Choices.

MR: I’ve watched that at least half a dozen times, and I still get emotional, especially since my wife’s very strong reaction to that video. Have you found other people have had such an impact from that video, and why do you think that is?

Tom: Yes, other people have had a similar reaction. I actually still get emotional when I think about it. The reason that video came to be was there was a young boy here in Hamilton who was hit in the crosswalk with a crossing guard.

He was walking home from school and the driver of a pickup truck just went right through.

The boy died a day later. That hit me really, really hard. He was about the same age as my child. I wrote this as somewhat of an open letter to City Council, highlighting all these things and just how ridiculous the state of our streets are and how it’s been falsely positioned – the wrong narratives – and these aren’t accidents. These are the results of specific choices that have led us here.

I turned the open letter into that video to capture, at such a base level of understanding, what some of the problems are. We are doing this, and no one is reining it in.

Yes. I still have a reaction because I think of that boy. His name was Jude Strickland.

I think it’s a powerful statement and it provides the right tone and balance that videos and content in our road safety space lack. They lack any emotion, any insight, awareness or understanding of the landscape that’s on our streets.

If you think about some public service announcements – that the police put out, the city puts out – they’re absolutely ridiculous. They’re atrocious. They’re poorly done. They’re not thought out. They’re checking boxes, and they’re checking the wrong boxes.

Putting this together was a counter-message and a reality check to what we’re doing. Why are we continually victim blaming? Why are we not regulating ridiculous vehicles? Why are we not building human-centric spaces for our children?

It’s all these things I tried to distill into 40 seconds of a video. It came from a really, really dark spot.

MR: It’s very, very powerful. Let’s look at the next video, Compromise.

MR: The contrast between the sense of entitlement of the lady driver versus the innocence of the child is really quite jarring. Was that your intention?

Tom: Yes, this is a small example of what we’re up against with auto ads. To many it’s just a regular auto ad, but it shows how reckless we position vehicles and driving in everyday life.

That city looks like any city you could be in, but everything is always covered off by a small legal disclaimer in two-point font at the very bottom of the screen.

It may not be some overdramatic horrifying Dodge auto ad, but the point is that all these ads promote reckless driving. When it’s done over and over and over and over again for 50, 60 years of advertising and marketing and being beaten into everybody, you start to accept that is okay.

Some people would say, “Well, it’s just marketing. It’s fantasy”. That’s true, to some respect, but not all consumer products take the lives of 40,000 Americans or 1.35 million people globally every single year. It’s much more than just fantasy marketing at that point when we get into auto advertising.

MR: The next video is called No Bravado.

MR: When I sent you my initial selection, you asked me to add this one. Why was that?

Tom: I really like it because it’s completely an anti-auto ad. It’s bicycles delivering the promises cars make. You don’t need celebrities. You don’t need big action sequences. You don’t need a huge budget. You don’t need all sorts of stunts.

You really just need the bicycle in its purest form, bicycles going right past all the vehicular traffic are stuck in themselves.

That’s a testament to the power of the mobility the bicycle and other active transportation modes offer.

MR: Let’s move on to the second feel-good ad now, which you’ve called Not Complicated.

MR: You would think the safety of our children would provoke action. Why do safe routes to schools, campaigns, and so on, have such an uphill battle?

Tom: It’s the ultimate question. Anytime we want to increase safety for people outside of the car, some councillors continually give in to the pressures of the constituents that feel they’re going to lose their right to unobstructed and speedy and expedient vehicular movement, which is apparently the only thing that matters in any city across the globe.

MR: One more video to go, Priceless.

MR: To me, personally, this was the most disturbing of all. You’ve used a technique Alfred Hitchcock used to use, that the villain is actually someone next door, someone socially acceptable, someone who looks nice, who doesn’t look like a villain. The very well-dressed, no doubt, socially responsible lady can become a child killer. Was that part of your motivation for this video?

Tom: That’s exactly it. It’s just the everyday violence that small little actions can lead to. It’s about highlighting how we are imperfect as drivers, and these small lapses in judgment and attention should not take the life of a person on the street, on a bicycle, or walking or in a car.

It’s a pitch for protected infrastructure for people outside of the car in safer spaces because essentially, we could all be that person. We don’t want to be that person, and I strive every day to not have a lapse in judgment or lapse in focus, but the reality is we’re imperfect. We’re humans. We’re going to make mistakes, so we need to ensure we have the infrastructure in place to allow for those mistakes to happen.

MR: We’ve watched five superb videos and seen five great still images. How would you like to see your work being used?

Tom: I would love to see messages like this more frequently in the mainstream. That would be my goal as a whole for this community of people that are making change, not just my messages.

We need to change the narrative in the mainstream culture around how we talk about people outside of the car, how we talk about safety for people outside of the car and really focus and reprioritise. For so long, what we’ve done is prioritised the predator and demonised their prey. That needs to change.

I would love for any of these messages to be out there in a broader sense. I would be happy for anyone’s messages that are attacking the root issues of road violence that are just devastating families every single day. It’s just nonstop. It’s a nightmare every day.

The worst part is we know the solutions. We know how to change things. We just refuse to. That’s one thing that motivates me, is that we know the solution. It’s about trying to get to that solution.

MR: If a local advocacy group wanted to take up some of your ideas and put it into a local context – an Australian or English context or whatever – how would you feel about them using your creative ideas and superimposing their local issues?

Tom: If anyone’s interested, happy to collaborate. I’m happy to connect.

MR: If some wealthy philanthropist or charity wanted to fund mainstream media campaigns based upon some of your work, how would you feel about that?

Tom: I would be very happy. That would be incredible. We’ve been getting inundated with the wrong messages for 100 years now and hyper-accelerated in the last 40 years with the auto advertising just owning every single media space available. Then our leaders in the police and the city just continually toe the line of victim blaming and shaming. It needs to change.

One of the big things that’s got me involved is when I started to go to council meetings and say “Can we try to improve this for some kids to get to school?”, it was positioned back to me that I was some radical, which I was not. That is what lit the fire under me, because I could not believe that wanting some kids to get to elementary school was considered radical.

It was such a damning indictment on who we prioritise and where we place value. If wanting kids to get to school is extreme, then something obviously needs to change. That’s what set me down this path and that’s what keeps me going.

MR: Where does this path go from here, Tom? What’s next for you in this space?

Tom: I don’t really know exactly. There’s a few things I’ve been doing, some lectures for different organisations, for some universities coming up in the next few months.

I’m happy to add my small voice to so much work that many people have done.