Cycling’s Stunning Advantages for Cities

Copenhagen, Denmark

Introducing good cycling infrastructure is one of the most cost-effective ways to fight climate change, according to a report produced by an international lobby group for better cities, Copenhagenize.

As international attention focuses on the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow this month, Copenhagenize took the opportunity to highlight how encouraging people to commute by bike, rather than other forms of transports, was potentially the most effective solution to cut carbon emissions.

“It’s difficult to predict precisely how many tons of CO2 you can save if you build a kilometre of bicycle lanes – the precise answer is highly complex and depends on many geographic, sociodemographic, economic and engineering factors,” Copenhagenize planning analyst Sam Gagnon-Smith says in his report.

“That being said, for a given municipal government in the developed world, there is likely nothing – dollar for dollar, euro for euro – better than bicycle infrastructure for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

Mr Gagnon-Smith quotes figures from the European Cyclists’ Federation that state the production and maintenance of the average bicycle over its useful lifespan results in emissions of five grams of carbon dioxide per kilometre travelled, or six grams for an e-bike.

The production, maintenance and fuelling of a car driven in a mostly urban environment amounts to 271 grams per kilometre.

“Getting someone to cycle instead of drive will therefore reduce that individual’s commuting-related carbon emissions by up to 98%,” he says.

“This figure is even higher for North America, where cars are larger, with more emissions during production and driving.

“For commuters that face steep hills and long distances, the e-bike provides a very clean option, at only six grams of CO2 per kilometre per rider for production and maintenance (this does not include any emissions resulting from the production of the electricity in the e-bike’s battery, which vary by country).”

Mr Gagnon-Smith said in developed countries the crucial factor in getting people to cycle is good infrastructure.

“Getting someone to cycle instead of drive will therefore reduce that individual’s commuting-related carbon emissions by up to 98%”

Sam Gagnon-Smith

Keep Cyclists Safe

“A good bicycle network will also connect cyclists with destinations and attract new users by making cycling a visible, physical reality on the streets. Good bike infrastructure can have an even greater impact when it is complemented by other kinds of policies – see for example Vienna’s hugely successful cycling promotion campaign,” he added.

“The bottom line, though, is cities that want cyclists, need to keep cyclists safe, and the best way to do that is with good street-level design.”

Copenhagenhize is an international consultancy offering bicycling planning, design and communications services for government and private developers. It assists with infrastructure design, cycling advocacy campaigns and education programs.

Mr Gagnon-Smith’s article says most of the carbon emissions from transport in the developed world come from passenger vehicles – mostly cars and pickup trucks, but also motorbikes, buses and trains.

“If cities can find an effective way to get people out of their cars, there is huge potential for progress on carbon emissions across all developed countries,” it states.

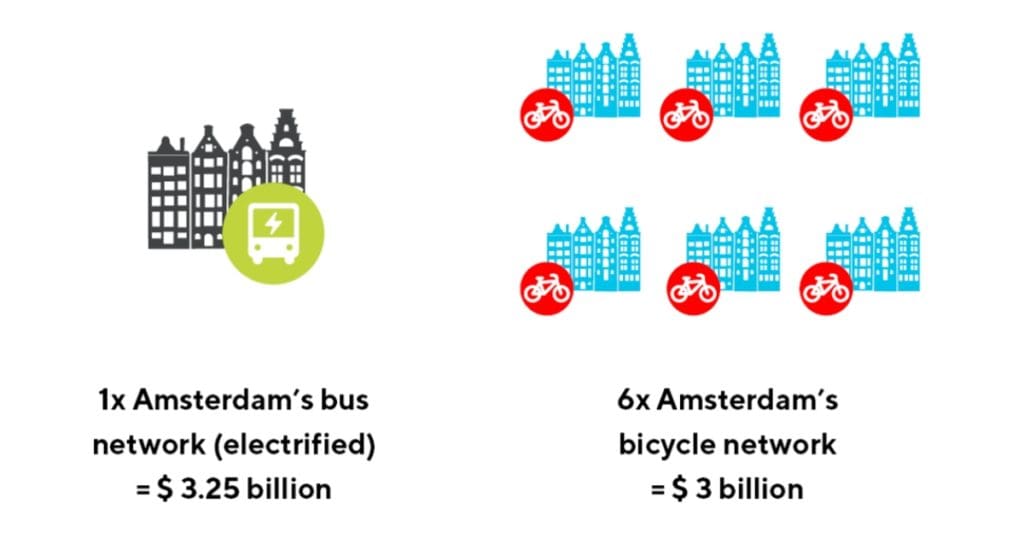

The article compares cycling to electric buses as an alternative to car travel.

“A fully electric bus costs around US$650,000 (A$875,891), including the infrastructure required to maintain and recharge it. A kilometre of protected bicycle lanes starts at around US$200,000 (A$269,529) for the basic-but-effective ‘paint and post’ model, but best-practice protected lanes, with full concrete protection, cost around US$1 million (A$1.348 million) per km, depending on conditions,” it says.

“Roughly speaking, then, you get three fully electric buses for the same cost as 2km of best-practice bicycle lanes. Let’s look at a real-world case to better compare these two options.”

Mr Gognan-Smith said Amsterdam’s world-class bus and tram network and its world-famous bicycle infrastructure provided a good case study. The city has about 500km of best-practice bike paths and 5,000 buses.

“Referring to the figures above, it would cost more than six times as much to build Amsterdam’s bus network (using only electric buses), as it would to build Amsterdam’s bicycle network,” he summarised.

“In other words, you could have a great electric bus fleet in one city, or Amsterdam’s bicycle network in six cities! And that comparison does not include the massive disparity in maintenance costs: an electric bus eats up about US$25,000 (A$33,692) in maintenance and servicing every year (not to mention the drivers’ salaries), whereas bike lanes only require cleaning and resurfacing, and less cleaning and resurfacing than the wider roads used by buses.”

In 2016, a team of researchers at McGill University estimated that adding 45km of bicycle lanes to Montréal’s network would have roughly the same effect on greenhouse gas emissions as replacing every diesel bus in the city’s fleet with hybrid buses and electrifying all the commuter railways.

“Forty-five kilometres of safe bicycle tracks, designed for a mix of busy and calmer streets, would cost somewhere around $10 million dollars. Replacing all the buses and electrifying the trains would cost well into the hundreds of millions of dollars.”

He said forward-thinking cities have recently fallen in love with bicycle infrastructure because they want clean air, healthy citizens and smooth and safe mobility on their street networks. However, cities such as Barcelona, Montréal, Tokyo, Bogotá, Paris and Taipei were looking beyond their own local benefits and were focused on the health of the whole planet.

C40 Cities – an alliance of almost 100 cities dedicated to fighting climate change – has stated cities are best positioned to fight climate change – as well as being most vulnerable to its impacts.

Cities are home to more than half the world’s population and an increasing proportion of carbon-generating activities, especially in the developed world, so they have the greatest potential and responsibility to fight climate change for the global community, the alliance says.

However, Mr Gognan-Smith said: “Money always seems to come up short for initiatives to fight climate change. Luckily for the cities that have been seduced by Danish and Dutch street design, they are already on the right track to reducing carbon emissions without breaking the bank.”

“For those cities that have not yet taken the plunge into designing for bicycles, they can look forward to massively reducing their emissions at a comparatively low cost while enjoying higher quality of life, more efficient use of time and space, and all the other familiar benefits of cycling citizens.”

European Cyclists’ Federation Report

The European Cyclists’ Federation, Cycle More Often 2 Cool Down the Planet!, was released back in 2011 and quantifies cycling’s potential emissions savings compared to cars and public buses.

Based on typical examples of conventional bicycles, e-bike, cars and buses, the report estimated the amount of CO2 emissions per person per kilometre for each option – incorporating the vehicle’s production, operation, maintenance and projected lifespan.

In the case of cycling, it also considered the amount of extra food riders consume to fuel their cycling and how that food is produced.

The study concluded the average bicycle journey produced 21 grams of CO2 equivalent.

This compared to 22 grams for e-bikes, 110 grams per passenger per kilometre for buses and 271 grams per passenger per kilometre for cars (the figures incorporated the average number of passengers on car and bus journeys).

The report also explored the disparity in emissions for meat-eating cyclists compared to their vegetarian and vegan peers, based on its finding that a 70kg adult bike rider burned 157 kilocalories per kilometre more than people travelling in cars. Sourcing that energy entirely from beef added 157 grams for every kilometre travelled, compared to 0.8 grams for soybean calories.

According to the study, emissions from transport would have to be reduced by 60% to play its part in achieving the European Union’s goal to reduce total greenhouse gas emissions by 80 to 95% compared to 1990 levels.

That would mean keeping annual transport emissions to within 308 million tonnes by 2050, which equates to 588kg per person per year. The total distance a person could travel while remaining within that limit, based on 2010 figures, is 28,000 by bicycle, 5,822km by bus, or 2,170 by car.